Episode Transcript

Transcripts are displayed as originally observed. Some content, including advertisements may have changed.

Use Ctrl + F to search

0:01

Radio Lab is supported by Progressive Insurance. What

0:03

if comparing car insurance rates was as easy as

0:05

putting on your favorite podcast? With

0:08

Progressive, it is. Just visit

0:10

the Progressive website to quote with all the coverages

0:12

you want. You'll see Progressive's direct rate, then their

0:14

tool will provide options from other companies so you

0:16

can compare. All you need to do

0:18

is choose the rate and coverage you like. Quote

0:20

today at progressive.com to join the over 28 million

0:23

drivers who trust Progressive. Progressive

0:25

casualty insurance company and affiliates. Comparison

0:27

rates not available in all states or situations. This

0:29

is very based on how you buy. Listener

0:36

supported. WNYC Studios. Imagine

0:45

your arms break off. And

0:48

your flesh turns to poison. And

0:51

your body begins turning strange

0:53

colors. Bright yellow

0:55

and tangerine orange. And you suddenly

0:58

get really good at math. Bugs

1:01

can do math? Mm-hmm.

1:04

There is a whole new season of

1:07

Terrestrials coming. Radio Lab's

1:09

family-friendly, ever so occasionally

1:11

musical series about nature.

1:14

On each episode, we tell you a story

1:16

about a creature that may seem fantastical. It

1:19

was like unbelievable. But is

1:21

entirely true. Oh

1:23

my goodness. And this season,

1:25

we scoured high and low all

1:27

over the globe. Underwater. In

1:30

the desert. In the wind. Underground. Up

1:32

to the Arctic. Oh, it

1:34

is cold. Braving dangerous terrain. All

1:37

right, mud's getting deeper down here, guys. Wild

1:40

beasts. It bit me several

1:42

times. There was blood everywhere.

1:45

And our own confusion. So

1:47

honey doesn't come out of bees? No,

1:50

it doesn't come out of bees. To

1:56

uncover... Wow.

1:59

The overlooked. Look at them. Overlooked

2:01

creatures. It's like a furball the

2:03

size of a grapefruit. They are

2:06

dancing on the comb, which is

2:08

extremely beautiful. And

2:10

overlooked storytellers. I didn't

2:13

really speak much, really

2:16

at all. I didn't speak at all. Waiting

2:18

quietly beneath our noses. There's moments

2:20

where you are made

2:22

to feel different. Who

2:24

have life-changing secrets to share.

2:27

It totally upended everything we

2:29

know about what we think

2:31

of as an organism. What

2:34

a witchy little ritual. Join

2:38

us for a nature walk that just might get

2:40

you to fall in love with this place again.

2:44

This hippo's barely up to my waist. I

2:46

mean, how realistic is it do you think

2:48

that we could get humans hibernating in like

2:50

20 years? I

2:52

think that it would be possible. Maybe,

2:56

I don't know. Come,

2:58

hang out with us. Oh,

3:00

oh, we grow together better than

3:03

a low. See you for it

3:05

for you. We grow together better

3:08

than a low. Terrestrials, Radiolab's ever

3:10

so occasionally musical series all about

3:12

nature. Hosted by me, Lulu Miller,

3:15

kids and adults. Welcome. All right,

3:17

good luck. Thank you. Get busy.

3:21

I don't know. Oh, my goodness. All new

3:23

episodes coming in September. Terrestrials on

3:25

the Radiolab for kids feed, wherever

3:28

you cast your pods. Yeah. It sounds like

3:30

a whole little party. Good

3:39

morning. Good afternoon. Good evening. Good

3:42

night. Depending on where you are,

3:44

when you are. This is Radiolab.

3:46

I'm Lotif Nasser talking to you

3:48

from right now, which is not

3:50

your right now, even though you are hearing it right

3:52

now. Anyway, I have an episode

3:54

for you, one we made a

3:56

few years ago. It is

3:58

both timeless. End time

4:01

full, time centric is maybe a better

4:03

word. It's an episode about time

4:06

because the vast majority of us,

4:09

no matter our philosophy of time, whether you

4:11

think of it as linear or

4:13

cyclical, time feels

4:16

static, right? Like no matter what you

4:18

use to measure it, a second, a

4:20

year, a millennium, those are constant units,

4:22

right? Like taking away the same

4:25

amount. Mm,

4:28

not so fast. The times,

4:30

as they say, are

4:32

a-changin'. Set your watches and

4:35

let's go. Wait, you're

4:38

listening. Okay. All right.

4:40

Okay. All right. You're

4:44

listening to Radiolab. Radio

4:47

lab. From WNYC. Hey.

4:50

See? Yeah. Rewind.

4:53

Hey, I'm Jad Abumrod. I'm Robert

4:55

Krowich. I want to tell you

4:58

a story about a discovery I

5:00

made. Not me, I just

5:02

learned about it from other people, but it

5:04

has made me completely reconsider what a year

5:06

means and specifically how big a year really

5:09

is. How

5:11

big a year it what?

5:14

How big a year really is. I

5:16

don't know what, how is a year, how long a

5:18

year is? Well, if you're confused now, I think I

5:21

can confuse you even more. I'm going to begin this

5:23

investigation by introducing you to a little creature in

5:25

the sea called a coral. Coral's a

5:27

shelly animal, a little creature. That's

5:30

Neil Shubin. I'm a paleontologist, an evolutionary

5:32

biologist at the University of Chicago. Just

5:34

like a clam, a clamshell has an

5:36

animal inside it, so

5:38

do corals. A little fleshy, wormy thing?

5:41

Exactly, and it wears its skeleton on

5:43

the outside. And because they sit in

5:45

the same place for their whole life,

5:47

they're really sensitive to local environmental changes.

5:49

Meaning what? Think about it this way.

5:52

Just think about what happens to a creature as it lives,

5:54

its life in the water, which is what these things do.

5:57

We live in a world of cycles, of cycles on

5:59

sun. Cycles. Temperature rises and falls.

6:02

Light rises and falls. The

6:04

tides rise and fall several times in the course

6:07

of a day. So

6:09

you think about what that means for creatures

6:11

living in water. What it means for corals,

6:13

says Neil, is that they're growing. They're slapping

6:15

on new skeleton, if you will, new shell.

6:18

In time with these cycles of rise and

6:20

fall, of light and dark, hot and cold,

6:22

and... Hello, hello. Hi. You

6:25

can actually see these changes written

6:27

onto their shells, maybe into their

6:29

shells. Emily. Andy. And

6:32

that's why Andy Mills and I called up our

6:34

pal Emily Graslie, whose job is... What

6:36

is it? I am the Chief Curiosity Correspondent

6:38

of the Field Museum in Chicago. That's

6:40

your actual title. The Chief Curiosity Correspondent,

6:42

yes. It is. You brought some corals,

6:45

did you? We have many corals. We have

6:47

corals all over the studio

6:49

desk right now. All right. All

6:51

right. Let's cut it. Because

6:57

when you cut into these shells... Oh,

7:00

it's warm. A little bit of

7:02

water. We can spritz it on there

7:04

and cool it off. Right off, you can see a

7:07

pattern. You

7:10

see these gray stripes. And they're

7:12

all, I mean, they're all different variations of gray,

7:14

but some are really dark gray and some are

7:16

tan. They're like bands

7:18

running either through or across the shell.

7:20

They kind of radiate out like the

7:22

bands of a tree. And between the

7:24

bands, there are spaces. You got

7:27

a stripe, then a space, a stripe,

7:29

then a space, a stripe, then a

7:31

space. But... When you hold it up close

7:33

to your eye... If you look closer

7:35

in between the stripes, you can

7:37

see sort of... Wow. You

7:40

can see the lines. Wow.

7:43

You can see that the spaces are

7:45

filled with faint little lines. And that's

7:47

where the piece of this story is

7:49

just so fascinating. Because

7:51

in 1962, a paleontologist... Professor John Wells... was

7:54

looking at some corals just like these. He

7:56

was just sitting there saying, okay, well, what

7:58

can we figure out from... in the choral shells.

8:00

So what he did is he did something

8:02

really simple. He says, well, golly gee, why don't

8:05

I count the number of little lines between

8:07

these bands? Just, you know, just to see. So

8:10

he starts counting as you know, 100, 200 lines, 300,

8:14

310, 320, and every time he counted. He

8:18

got a number around, around 360, 365.

8:23

Wait a second. Familiar

8:25

number, no? Doesn't take a whole lot of

8:28

inference that hey, maybe

8:30

those individual rings represent

8:33

a daily pattern. Meaning each of

8:35

these little lines actually equaled a

8:38

day. And why, they're

8:40

not just making a gray mark after 365. No.

8:43

What are the gray lines? Well, the thicker lines are

8:45

the times of the year when the choral grows a

8:47

lot. But if you've got a summer choral that it

8:50

grows a lot in one summer, then it goes quiet,

8:52

then it grows a lot the next summer. So that's

8:54

again, that marks the year. Those big bands are kind

8:56

of like, na, na, na, na, na, na, na, na,

9:00

Happy New Year. Na, na, na, na,

9:02

na, Happy New Year. Na, na,

9:04

na, na, Happy New Year. They're actually calendars and clocks

9:06

inside each of these things. You just have to know

9:08

how to read them. So this guy,

9:10

Professor Wells. What he did was then, this is

9:12

the really bold bit

9:15

I thought, which is he

9:17

then said, well, okay, that's a living choral.

9:19

Let's look at some fossils. He

9:23

was after all a paleontologist. Yeah, so he

9:25

was at Cornell University at

9:27

Cornell University surrounded by rocks

9:29

around 370 or so million years old. And

9:34

he collected some nice corals and there are a

9:36

lot of nice coral fossils known from there. And

9:38

he opened up these ancient skeletons. And he did

9:40

the count. Found 100 days, 200 days. He

9:45

was expecting 360 to 365. Then

9:52

lo and behold, he found 400. Between

9:54

400 and 410. Really?

9:58

Yeah, and he looked at lots of specimens. That number. the

10:00

400 number kept showing up. What does

10:02

that mean? Well, that means

10:05

that it's now

10:07

reasonable to think that back in the

10:09

day, you know, 380

10:11

million years ago, there were more days

10:13

in a year. And

10:18

he published a paper saying more or less that. And

10:20

right away, clam

10:22

scientists said, well, if that's true for corals, and it's

10:24

got to be true for my animal, the clam, and

10:26

the oyster people said, well, it's got to be true

10:28

for oysters and muscle folks has got to be true

10:30

for muscles. This paper set off a bit of a

10:32

cottage industry of folks applying this

10:34

technique to other species. In

10:37

looking at these other species, they found

10:39

that the general trend is absolutely correct.

10:41

That when you compare modern animals to

10:44

ancient animals, you will find they record

10:46

the old ones more days in

10:48

a year. So you go back to a time period

10:50

called the Ordovician, which is about 450 million years ago.

10:54

A typical year had about 415, 410 days in it. If

10:59

you go to the time period I work on in the Devonian,

11:01

about 360 million years, probably about

11:03

400. So what you see

11:05

is the number of days in a year has

11:07

declined from over 400 to what we have

11:10

now, which is 365. So

11:12

we have lost 40 days since the... Yeah,

11:14

since creatures first started to walk on land.

11:17

So now comes the obvious question. Why?

11:19

Why would there be more days then than there are now?

11:22

Wait a second. Wait a second. A

11:24

year is a trip around the

11:27

sun. That's a trip. Yeah, try

11:29

it. And days are when we spin

11:31

around and says we're going around the sun. Okay. So

11:34

maybe if you want to squeeze more days into a year, maybe

11:36

it just means the trip around the sun took

11:39

longer back then? Well, if you ask astronomers

11:41

about that, I asked Chris Impey at

11:43

the University of Arizona and he says... There's

11:45

no sense that the length of time it

11:47

takes the Earth to orbit the sun

11:49

is changing. Because the Earth's orbit

11:52

around the sun is basic physics and it hasn't

11:54

really changed significantly. He's pretty sure of that. So

11:57

then what is it? Well, Chris says the answer takes

11:59

us back about... and a half

12:01

billion years to a time when

12:03

the Earth was very young. So there was this

12:05

crazy period of time lasting about 50 million

12:08

years. Which they called

12:10

the Great Bombardment Period. There

12:14

was still a lot of debris left over from the

12:16

formation of the solar system. So the

12:18

meteor impact rate was thousands of times

12:20

higher. The Earth was still like a

12:23

tacky magma. And

12:25

so there was a hail, brimstone,

12:27

endless rain. I mean,

12:29

kind of crazy time, really. And a bit of that

12:31

mayhem, of course, we think gave

12:34

birth to the moon. There was a huge

12:36

collision, and a rock about the size of

12:38

Mars banged into us,

12:40

flung a hunk of Earth's shrapnel

12:42

into orbit. And those pieces coalesced

12:44

and became our moon, which

12:48

is now sort of parked right next to us.

12:50

And so it sort of tugs us around in

12:52

a kind of hefty way. And the biggest... I

12:55

thought we tugged the moon. Oh,

12:57

it works both ways. We tug the moon,

12:59

and the moon tugs us, and the force

13:01

is actually equal. So it's kind of like

13:03

a dance. It's a dance. I tug the

13:06

moon, and the moon tugs me. Exactly. It's

13:08

a celestial waltz. And

13:15

it's that dance, that waltz, that explains why

13:17

the Earth used to have 450 days in a year,

13:21

then 400 days in a year, and now only 365. Well,

13:25

I don't see how this explains anything yet. Well, first

13:27

of all, let's just remember what a day is. A

13:30

day is a full spin of the planet, from the

13:32

sun coming up in the morning, then going down, coming

13:34

up the next morning. So one spin, a total spin,

13:36

equals a day. Yes. We all know that.

13:38

Now, today we make 365 of these spins, as we orbit the sun.

13:42

That would be a year. Right. But back when

13:45

the Earth was born, when it was all

13:47

by itself dancing alone, that in those days

13:49

did spun faster. It

13:52

was making more of these spins as it went

13:54

around the sun, so a year had more days

13:56

in it. But then, along comes

13:59

the moon to join... the dance and now here's

14:01

the key according to Chris. Earth

14:03

is spinning faster than the moon is

14:05

orbiting it. A dance party takes a

14:07

month to come around us. We take

14:09

fyoom 24 hours, fyoom. And

14:12

you know how it is when you're dancing

14:14

with a partner who's slower than you are?

14:17

Then you have to you have to tug

14:19

them along, which is what has happened here

14:21

gravitationally. We are constantly tugging the moon along.

14:23

It is constantly dragging us down. There's a

14:26

transfer of energy here that over billions of

14:28

years has caused the earth spin to slow

14:30

down just a little bit, a teeny, teeny

14:32

bit. And as the spin has slowed, well,

14:35

our days have gotten longer. And if you

14:38

do the math, you calculate that the day

14:40

is getting longer by 1.7 milliseconds

14:43

each century. 1.7

14:45

milliseconds each century. What this means on

14:47

a daily basis is that today was

14:49

54 billionths of

14:51

a second longer than yesterday.

14:54

And the day before that was 54 billionths

14:57

of a second longer than the day before. And

15:00

the day before that was 54 billionths of

15:02

a second longer than the day before that, which was

15:04

54. And if you extrapolate that out

15:06

over the millions of years people

15:08

like me think about... That's Neil Shubin

15:10

again, the paleontologist. That becomes quite

15:13

significant. So you're telling me that today

15:15

is the shortest day of the rest

15:17

of my life? Yes. Andy

15:20

worries about these things. Well, you're not going to live longer

15:22

because of this, I'm sorry to say. No,

15:24

so this moon dance does not affect the

15:26

ticking of time. It just affects what we

15:28

choose to call a day. And by the

15:30

way, one of the consequences of this dance

15:32

is as we lose a little energy to

15:34

our moon every year, and then it

15:36

picks up a little energy from us because these

15:38

things are always equal. Think about like when you

15:40

throw a ball, the more energy you use, the

15:42

further the ball is away from you. Well,

15:45

as we add a little more

15:47

energy to the moon, the moon

15:49

very slightly moves a little

15:51

further away from us. Every year it's

15:53

about... A couple of inches. According to

15:55

Chris. The length of a worm. Really?

15:57

So the moon is getting a worm's

15:59

distance. further away from us every

16:01

year. Yeah. And he says

16:03

if you go back about four billion years...

16:05

The moon was originally about 10 times closer

16:07

than it is now. 10 times closer? Imagine

16:10

the moon looking 10 times bigger than it

16:12

does now. That would have been crazy. Also,

16:15

the days would have been

16:18

six hours long. Six hours

16:20

long? To

16:23

me, what this says is

16:26

that everything that we take

16:28

for granted as normal

16:31

in our world. Ice

16:33

at the poles, seas in certain

16:35

places, continents configured the way they

16:37

are, the number of days in

16:39

a year. All that is

16:42

subject to change. And all that

16:44

has changed. All that has dramatically

16:46

changed over the course of the history

16:49

of our planet. And that includes how

16:51

we measure time itself. So,

16:53

you know, when I'm sitting in a hole in the middle of the

16:55

Arctic digging at a fish fossil, every now and

16:57

then, you know, I pinch myself and say, here I

16:59

am in the Arctic digging at a

17:02

fish fossil, you know, that lived in

17:04

an ancient subtropical environment. You

17:06

know, the juxtaposition between present and past

17:09

sometimes is utterly mind-blowing. But it's very

17:11

informative about our own age and that

17:14

we, you know, we think things are

17:16

eternal, but they're not. Everything

17:18

is subject to change. Change is the way of

17:20

the world. We

17:23

are going to change now to a break, but

17:25

we've got more coming up after that. We

17:31

all have questions. Do you enjoy your bowel movements? No. You

17:34

have questions. Why were

17:36

you laughing? I don't know. We

17:38

have questions. What makes someone successful? Why can't

17:40

you sell your blood? Why do vegetables spark

17:43

in a microwave? No matter the question. How

17:45

can you be a scientist and not know

17:47

the answer to that? And

17:49

thanks to support from listeners like you. Does time

17:51

slow down with your phone? Can we make a

17:54

living thing? Can babies do math? There's a radio

17:56

lab for that. A little CRISPR work. Join the

17:58

lab and spread the word. on

18:01

t-shirts nationwide. New t-shirts

18:03

available now. Join the lab, check out the

18:05

t-shirt design, and

18:07

pick your favorite color over at radiolab.org.

18:30

You can also use your Apple Card in the Wallet app. Subject

18:32

to credit approval. Savings

18:34

is available to Apple Card owners. Subject

18:36

to eligibility. Apple Card

18:38

and Savings by Goldman Sachs Bank USA, Salt Lake

18:40

City Branch. Member FDIC. Terms

18:44

and more at applecard.com. Radiolab

18:46

is supported by Betterment. Do you

18:49

wish your money could be motivated? That it

18:51

could get up to rise and grind and

18:53

work hard for you? Don't worry. Betterment

18:56

is here to help. With

18:58

the automated investing and savings app that makes

19:00

your money hustle. Their automated

19:02

technology is built to help maximize returns. Meaning

19:05

when you invest with Betterment, your money can auto adjust

19:07

as you get closer to your goal, rebalance if your

19:09

portfolio gets too far out of line, and your dividends

19:11

are automatically reinvested. That can increase the potential for compound

19:13

returns. In other words, your money is working like a

19:15

dog, while you can be sleeping like one. You'll

19:18

never picture your money the same way again. Betterment,

19:20

the automated investing and savings app that makes

19:22

your money hustle. Visit betterment.com

19:24

to learn more. betterment.com, the automated

19:26

investing and savings app that makes your money

19:28

hustle. Visit betterment.com to

19:30

get started. Investing involves

19:32

risk. NYC Now

19:34

delivers the most up-to-date local news from

19:37

WNYC and Gothamist every morning, midday and

19:39

evening. With three updates a day, listeners

19:41

get breaking news, top headlines, and in-depth

19:44

coverage from across New York City. By

19:47

sponsoring programming like NYC Now, you'll

19:49

reach our community of dedicated listeners

19:51

with premium messaging and an uncluttered

19:53

audio experience. Visit sponsorship.wnyc.org

19:55

to get in touch and

19:58

find out more. Hello

20:03

again, you're listening to Radiolab. I'm

20:05

Lathif Nasser. We are discussing the

20:07

flexibility, the surprising flexibility of time

20:09

today. And in the first segment,

20:11

we learned all about how coral

20:13

has marked the ever-changing march of

20:15

time, how days were once shorter,

20:17

years once longer. Now

20:19

we're gonna pivot to a more, I mean, I

20:21

don't know. It's

20:24

like taking that idea of time flexibility and

20:26

just taking it to an absurd, absurd

20:30

place with

20:32

our host emeritus, Robert

20:35

Krawich. So I just wanna play

20:37

you a little bit of a, can we do this?

20:39

Can we just add an end to the end? Cause

20:41

that's what I'd like to do. Yeah, sure, yeah. I

20:43

was talking to Neil deGrasse Tyson, who's an astrophysicist and

20:46

who thinks about spin, which we've just thought about, thinks

20:48

about the inner solar system, which

20:50

we've just thought about. So here's

20:52

him and I talking about holding

20:56

on to time. It's

20:59

a little goofy, but here it is, just for the fun

21:01

of it. So if you're on

21:03

earth and you're walking around Quito on

21:05

the equator, if

21:08

you're walking at four miles an hour, your

21:11

day will go sort of the normal way. The

21:13

sun will rise behind you, go overhead, and then

21:15

go down the other side. Well, if you're stationary,

21:17

it will be the 24 hour day, yes. If

21:20

you started walking on the equator, depending

21:23

on which direction you walked, your day will either

21:25

last longer or shorter.

21:29

So if you walk west,

21:32

the faster you walk, the longer your day will become. You could

21:35

walk at a pace where you have a 25 hour day, a

21:37

27 hour day. There's a speed

21:39

with which you can walk on the equator and

21:42

the earth going west, where your day lasts forever,

21:45

and that is the rotation rate of the earth. You

21:48

would have compensated for the rotation rate of the earth. Roughly

21:50

what that would be, a gerbil. A gerbil running on a

21:52

beach ball, a rotating beach ball. So that would, on the

21:54

top of a beach ball. So that

21:57

speed for the equator is about 1,000 miles an hour. So

22:00

the equator moves a thousand miles an hour and that gives us

22:02

the 24 hour day. If

22:05

you want to go a thousand miles an hour in the opposite

22:07

direction, you will stop the day. The

22:09

sun will never move in the sky and your day will last. Superman

22:14

did that once I think when he had this thing

22:16

with Lois. Superman would have so messed up everybody on

22:18

Earth for having stopped the rotation of the Earth, reversed

22:20

it and then set it forward. Yes, he did that.

22:23

He would have scrambled all, anything not bolted

22:25

to the Earth would have been good.

22:27

Really would have flown off? Yeah, yeah. So

22:29

depending on your latitude and equatorial residence, if

22:31

you stop the Earth, they were going at

22:33

a thousand miles an hour with the Earth. You stop

22:36

the Earth and you're not seat belted to the Earth,

22:38

you will fall over and roll due east a thousand

22:40

miles an hour. In our mid latitudes, we're

22:42

in New York, you can do the math, moving about 800 miles

22:44

an hour due east and

22:47

stop the Earth. We will roll 800 miles an hour

22:49

due east and crash into buildings and other things that

22:51

are attached to the Earth. That are attached to the

22:53

Earth. All right. But let's, going back

22:55

to Venus now. Oh, you want to go to Venus? Isn't this

22:57

enough for you? I want to take the whole point was to

23:00

go to Venus because it's so different there. Yeah, on every way.

23:03

No, it's about the same size and about the

23:05

same surface gravity, but that's it. It's

23:09

900 degrees Fahrenheit. It's a runaway

23:11

greenhouse effect. It is a heavy

23:13

volcanic activity that repaves the surface

23:16

periodically. So there are very few craters on Venus.

23:20

Just unpleasant in general. Unpleasant. Rotates

23:22

very slowly. Well, that's why I want to stop.

23:24

So how slowly does it rotate? I don't remember

23:27

the exact number. It's like four miles an hour

23:29

or something like that. Yeah, it's some very slow

23:31

rate at its equator. Slow

23:34

enough so that you don't need special,

23:36

you don't need airplanes to stop the

23:38

sun. You don't need special

23:40

speed devices. You could probably trot and

23:42

stop the sun on the horizon or wherever the sun

23:45

is. So if you're that guy from Jamaica, what's his

23:47

name? Usain Bolt. Usain

23:49

Bolt. Like, and you happen to

23:51

be on Venus for a little

23:53

while and you decide to go for a run. What

23:56

happens to Usain during the run? So

23:58

normally there's so much. would rise in

24:00

one direction instead in the other. Depending

24:03

on which direction you chose to run

24:05

in, you could reverse your day and

24:07

have the sun rise in the opposite side

24:09

of the sky than it normally would. But

24:12

I think Venus is rotating slowly enough that you wouldn't

24:14

have to be Usain Bolt. I'd have to check my

24:16

numbers on this. Oh, I don't think you would. Maybe

24:19

in order to have the sun actually sort of

24:21

seem to go backwards, that's what you're saying, is

24:23

the sun to go backwards. So

24:26

you'd be having lunch, you're Usain Bolt, and you go to

24:28

the side, now I'm gonna run, and

24:30

the sun's going backwards towards the morning on the horizon.

24:33

Yes, you can reverse the sun, that's correct. In fact.

24:35

Wow, that is a really good reason to

24:37

sprint, I

24:39

think. Well, but who cares about the sun anymore?

24:42

Me, I was saying, I go up to you and I

24:44

think. Is the sun telling you when to eat lunch? I

24:46

don't think so. Your stomach is telling

24:48

you when to eat lunch. You're saying, okay, Usain,

24:50

you eat breakfast, but you wanna have lunch real

24:52

soon? Run, so that the sun is now at

24:54

the top of the sky, so now you can

24:57

legally have lunch. You

25:00

are not buying my poetic premises

25:03

at all today. This is the 21st century,

25:05

Jack, and the sun

25:07

is, we wake by alarm clocks,

25:09

not by roosters and sunlight, I'm

25:12

sorry. Just doesn't

25:14

work that way. I wish I could help you

25:16

out by thinking, let's suppose. I am not gonna

25:18

depend on running so that this, on Venus, to

25:21

get the sun in the middle of the sky at

25:24

my command, so that I can have lunch. Okay,

25:26

all right, but let's suppose you're a rooster

25:28

and you like to crow at dawn. That's

25:30

just a deep feeling in you. You could

25:32

totally mess with a rooster this way. Yes,

25:34

that's what I wanna do. Usain Bolt carrying

25:37

a rooster with it. Usain Bolt carries a

25:39

rooster on Venus. He does a remarkably fast

25:41

sprint. The rooster, having started the run in

25:43

the middle of the day, well past the

25:45

crowing period, feels a strange compulsion to crow

25:47

two hours into the run. Because

25:50

he ran backwards to the sunrise, rather

25:52

than to the sunrise. Well, he ran forwards, but the

25:54

sun went backwards relative to him. Yes, he ran in

25:56

the other way to reverse the

25:58

sun back to sunrise.

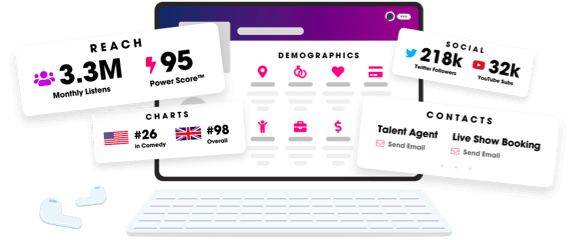

Unlock more with Podchaser Pro

- Audience Insights

- Contact Information

- Demographics

- Charts

- Sponsor History

- and More!

- Account

- Register

- Log In

- Find Friends

- Resources

- Help Center

- Blog

- API

Podchaser is the ultimate destination for podcast data, search, and discovery. Learn More

- © 2024 Podchaser, Inc.

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Service

- Contact Us